The Pacification Campaign 197 - 185 BC

The often dubious loyalty of Spanish auxiliaries during the Second Punic War had proved a major problem for both Rome and Carthage. While the Celtiberians had naturally swung towards Scipio's Romans in the closing years of the war, they were quiet for only a few years before insurrections against Roman authority across Spain became a serious threat.

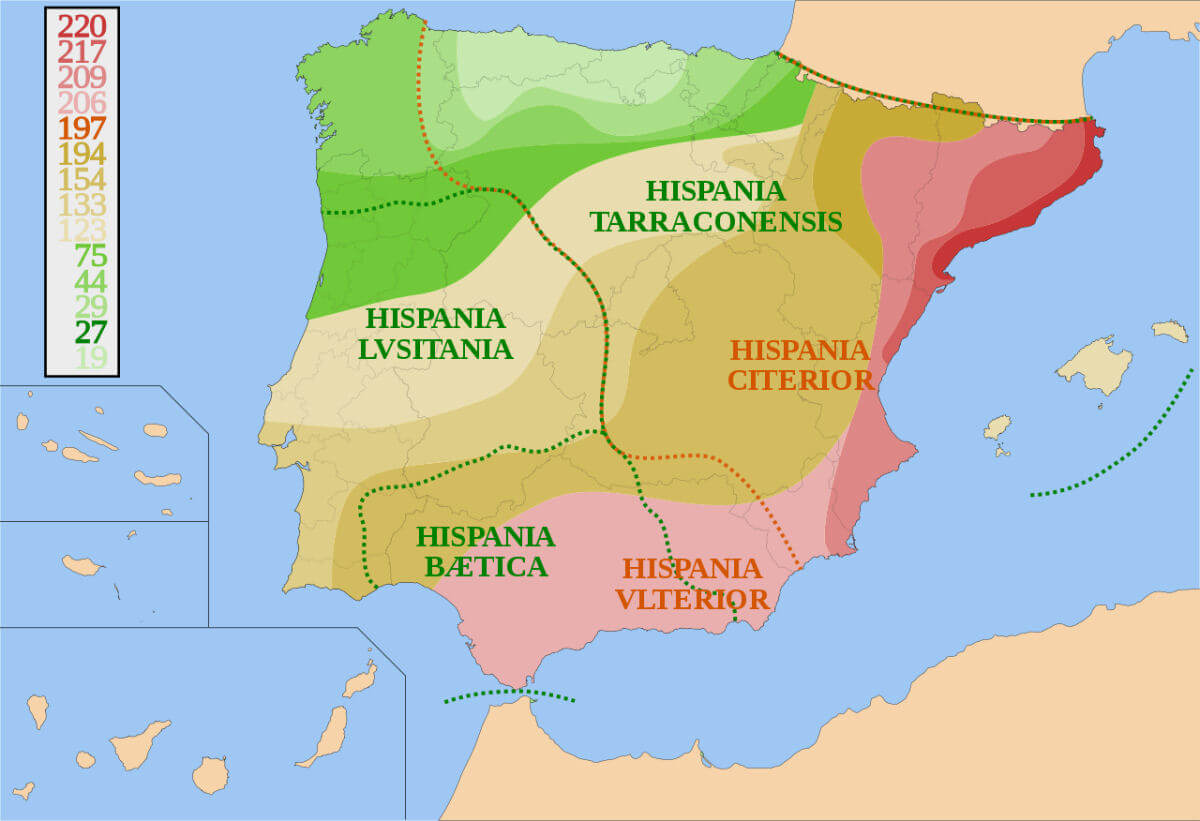

In 197 BC, the Senate divided the conquered territory into two Praetorian provinces, Hispania Cilteria or 'Hither Spain' in the east and Hispania Ulterior 'Further Spain' in the south.

I, HansenBCN, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A map showing the conquest of Hispania from 220 BC to 19 BC, and the provincial borders

Initially, the Senate did not consider these tribal rebellions a major threat, writing them off as raids which could be dealt with quickly and easily. Such overconfidence would prove disastrous; in the first battle of what would become a greatly protracted campaign, the Proconsul Sempronius Tuditanus was defeated and killed at an unknown location.

In the two years following the defeat, matters in Macedonia and Greece prevented immediate vengeance until 195 BC, when the Praetor Minucius Thermus inflicted a serious defeat upon the Celtiberians at Turda, killing 12,000 as well as capturing their general, Budar. In that same year the other Praetor, Marcus Helvius, held off and defeated a Celtiberian ambush at Iliturgi, despite being heavily outnumbered.

However, before the year drew to a close, the Celtiberians began mustering a new army of such massive size that it became apparent that it would take more than a Praetorian force to deal with them. Thus, the Consul Marcus Porcius Cato (known now as Cato the Elder to distinguish him from his great-grandson and enemy of Julius Caesar, Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (Cato the Younger)) was sent with a significantly larger force to hither Spain to take command of the situation.

After reassuring his remaining Celtiberian allies of their protection, Cato marched against the enemy camp at Emporiae, where he tested the strength of his raw recruits by sending them in raids against enemy foragers. These were conducted with the greatest success, so much so that the enemy eventually shut themselves up in their camp and refused to venture out at all.

With the confidence of his men elated, Cato now looked to press for a decisive battle, sending three cohorts to go up against the enemy gates and goad them into coming out. The plan worked, and when the enemy came bursting out for action, Cato's pre-positioned cavalry fell upon their flanks immediately.

Nevertheless, the enemy put up a valiant resistance, turning the battle into a prolonged slogging match until Cato finally got the upper hand by sending in his reserves. Forcing the enemy back into their camp, the Romans attempted to pursue them inside but came under heavy missile fire, making little headway until Cato noticed that the left gate was poorly defended.

Gathering the hastati and principes of the II Legion, he directed a charge against the gate, which the few defenders were incapable of holding off. Having broken inside their lines, the enemy now panicked and attempted to flee. Most were killed at the gates when they became stuck while all trying to escape at once.

The controversial historian Valerius Antius - controversial according to Livy anyway (Related External Link: classicalstudies.org) - quotes 40,000 of the enemy as being killed, but Cato himself fails to provide a figure, and is simply credited with saying that many were killed.

In any case, the action was temporarily decisive, convincing all Celtiberian settlements north of the Ebro to surrender. The Senate expected that such a massive blow to Celtiberian manpower would bring the war to close but, in reality, it was just the beginning.

David Mateos García, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

The remains of a Roman wall at Emporiae, Spain

In the years following Emporiae, Spanish insurrections were put down brutally and efficiently, with Celtiberian forces suffering further defeats at Ilipa and Toletum in 193 BC. Despite this success, the Roman forces failed to make a significant impact upon enemy uprisings. As Hannibal had eventually been forced to run constantly around Italy, dealing with multiple Roman armies, the Romans now too found themselves fighting a war which was always shifting.

Despite success on the battlefield, flaws in the militia army of the Roman Republic were starting to become apparent. The citizenry showed little interest in the far-flung campaign, as not only did the Celtiberian tribes not pose any threat to Italy, but the regular allure of booty and plunder had failed to meet many soldier's expectations. As a result, there were few volunteers, while those that were already involved became increasingly disgruntled by the lack of forward progress and recognition back home.

To put further strain on the Spanish Campaign, the Senate was forced to shift its military priority to the Eastern front when Antiochus III invaded Greece in 191 BC.

With ever-decreasing support and morale, it wasn't long before setbacks started to occur. In 190 BC, 6,000 Romans were killed after their camp came under attack at Lyco while in the following year, the Praetor Lucius Baebius was defeated and killed at Massilia.

Redemption for these losses was achieved in 186 BC, when two Celtiberian armies were checked at Hasta and Calagurris, but this was immediately overshadowed the following year when the combined Praetorian armies of Calpurnius Piso and Quinctius Crispinus were smashed at Toletum, for the loss of 5,000 men.

Despite this humiliating defeat, it was the only thing capable of making the Senate sit up and pay attention to the ailing campaign.

The defeated Praetors were eager to redeem themselves, but knew that their army in its present shape was low on supplies, allies, morale and training. Thus, envoys were sent out to reaffirm alliances with friendly Celtiberian tribes and recruit auxiliaries, while the Praetors began a rigorous training campaign for the legions.

At the end of 185 BC, when it was felt that morale had been sufficiently revived, the two Roman armies marched towards the Tagus River where the 35,000 strong Celtiberian force - the same which had defeated them earlier - was encamped on the hills of the opposite side.

Crispinus and Piso boldly moved their forces across the river but, despite being in plain view of the enemy, the Celtiberian forces did not take the prime opportunity to attack them in their vulnerable state, perhaps a result of their disorganized command structure. Having crossed safely, both sides formed up for battle, with the Praetors placing their best legions - the 5th and the 8th - in the centre, with the cavalry taking up their usual spots on the wings.

When the battle commenced, the Celtiberians initially made little progress but, mid-battle, managed to reorganize their infantry ranks into a wedge formation, which put the action back in their favour. As the front lines of the legions began to crumble under the enemy counterattack, Piso and Crispinus each took personal command of the cavalry wings and simultaneously led flanking attacks against the enemy wedge.

Calpurnius' charge was particularly devastating, and the carnage that he inflicted boosted the morale of the legions, which at once began to hold their ground before surging forward with renewed vigour and courage. Hard-pressed on all sides, the Spanish wedge collapsed, and the fugitives fled in disorder to their camp.

The Romans followed closely in pursuit and slaughtered many more of them inside. It is said that only 4,000 men out of their entire force escaped, while 132 standards of the enemy were also captured. By comparison, the Romans lost 750 men, including five military Tribunes.

The victory at Tagus was exactly what the Senate hoped for... decisive, with Spanish tribes everywhere surrendering to Roman authority. While Spain itself now seemed to be pacified, peace would last only four years.

Did you know...

Celtiberians spoke a language inherited from Continental Celtic, related to Gaulish and Lepontic. The main difference was that Celtiberians acquired much of their phonetics and lexics from non-Indo-European Iberian languages.