Ancient Roman Education

Of the many cultural and technological advantages that ancient Rome held over its competitors, the education of its citizens is not one that immediately comes to mind.

However, there can be no doubt that the Roman education system resulted in citizens, politicians, and generals who were all better equipped to meet challenges and solve problems than those in many other ancient societies.

For example, the literacy rate in ancient Rome was astronomically higher than surrounding areas outside of Roman influence, which has an incalculable effect on labor efficiency.

By the time of the Imperial Period, they had developed a system of formalized education that would not only continue to enrich their own citizens, but formed the basis for the Western educational systems that are in use today.

Education in the Early Republic

In the first days of the Roman Republic, Roman family life was dominated by the practice of patria potestas, whereby the father was wholly and completely responsible for the upbringing of each of his children, including education.

In theory, the father would teach each of his children directly or assign a family member to do it, should he be unable or unwilling to do it himself. In practice, however, there was no real social expectation that children actually be educated at all. The one exception was if a person was seeking to enter political life, in which case everyone expected them to be thoroughly educated.

This decentralized institution where a father is left to educate children himself, or simply decide not to do so, obviously had the effect of providing very different education levels for different children. A lot of the time this had to do with wealth and social class, but there were plenty of examples of rich fathers who saw no use in educating their children, and poor fathers who thought that education was their children’s best chance of a better life.

One unexpected aspect of this uneven educational approach was that girls from wealthy families were often educated alongside their male siblings. While ancient Rome would always be male-dominated, this access to education would carve out a sphere of independence for Roman women that was seen in very few other places in the ancient world.

Education in the Late Republic and Imperial Period

In the 3rd century BC, Rome would begin to conquer Greek areas of the Italian peninsula and then engage Carthage in the First Punic War. Both of these events had the effect of heavily exposing Rome to Greek culture and influence on a large scale for the very first time.

Countless Greek artisans and craftsmen were displaced to Roman lands following their conquest. Many Romans were immediately taken with certain Greek activities and practices, some of which were hundreds of years old by this time.

One of these was the practice of public education by professional tutors and in academies, along with the accompanying social expectation that all children receive some form of formal education (a Greek idea that remains popular worldwide to this day).

With the Hellenization of Rome came the very first Greek tutors. These men were often slaves gained in the spoils of war and were placed in the wealthiest and most prominent Roman families to help educate their children in the Greek fashion.

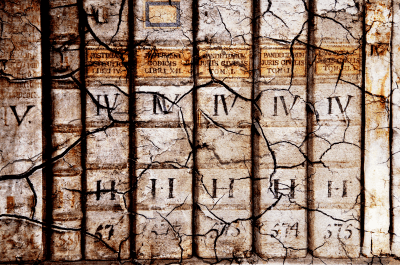

Since the Greeks had a long tradition of literature, Greek tutors were able to use these texts to teach the children the same lessons and themes year after year. Before this, Roman society was unable to develop this same literary educational method on their own because they did not have their own tradition of literature.

Alongside simple arithmetic, reading, and writing, complex Greek subjects such as philosophy, logic, ethics, poetry, astronomy, geometry, and political science entered the Roman world for the first time. However, Roman society saw the fields of music and athletics, which were very important to the Greeks, as unworthy of study.

At the same time, the ancient Roman institution of patria potestas was deteriorating in social importance. This meant that the social convention where a father was completely responsible for the upbringing of his own children was not as extreme as in prior centuries. The result was that Roman leaders began to think of the education of Rome’s youth as a matter of state importance rather than confined to the private family sphere.

Following the Greek example, many of these leaders saw that a formal system of schools and academies with a consistent curriculum was the best way to create educated Roman citizens, which would only serve to strengthen the Republic.

Before long, Rome had a great number of these academies with tiered courses of study, where advancement was more dependent on ability rather than age. Furthermore, education became expected, though never mandatory, for all male children.

Gender & Education

While Roman society developed a rather sophisticated and modern system of education, participation was almost completely limited to male children. The education system was quite accessible to boys, even those who were from the lower social classes, but girls were not admitted except in very extreme circumstances.

This meant that the study of certain topics, particularly those surrounding politics and war, were completely closed to female students.

Even though the formal school system was not accessible to girls, there was still a robust tradition of educating young women in Rome. This practice would continue in the old, pre-Greek method, where a girl’s education would be handled by her family or close friends.

In some cases, a family could even hire a private tutor to educate their daughter, resulting in an education that might even be better than the one publicly available to boys.

As such, women in the upper echelons of Roman society were often highly educated and politically savvy.

The topics of a woman’s education would vary from those given to men because of the different roles that women had to play in society. Girls were given lessons that would help them efficiently run a household as adults. This would include traditional domestic tasks like home maintenance and food preparation, but also included what we would call financial and business training, like investment and labor management.

This is because women were traditionally responsible for the family estate while men were otherwise occupied outside of the home. Women in Rome also maintained independent financial assets after marriage, which necessitated some of this training.

Click here to find out more about women in ancient Rome.

Tiers of Education

Early Childhood & Moral Education

From the earliest days of the Roman Republic, children’s education began with their parents teaching them the basics about moral conduct and discipline. This included learning not only right from wrong, but also understanding one’s roles and responsibilities as a member of a greater society. This pietas, or sense of societal duty, was different for boys and girls.

For boys, the greatest sense of devotion was to the state, while girls were taught that duty to one’s family, particularly their father and/or husband, was paramount. This practice of moral education in early childhood by family members persisted even after the adoption of formal schools.

Ludus

The first primary school that young boys attended at or around age six was called a ludus literarius, where they would be given instruction by a teacher whose job it was to do so. The focus of this stage of education was the essential skills for functioning in Roman society, such as reading, writing, basic arithmetic, and measurements.

Instead of dedicated buildings, Roman public policy allowed for creative uses of space to accommodate these ludus schools. Some of them were rotated between empty warehouses that were not currently in use, or even held in the middle of a public street.

There were no examinations or formal grades given, but a student’s performance was either praised or corrected by the instructor, creating hierarchy and competition among them.

The time a boy would spend being instructed in a ludus school varied based on their proficiency levels. In fact, boys from wealthy families often skipped this stage altogether because their parents could afford a tutor for private instruction.

If a student showed promising ability, and his family possessed the requisite funds, he could move on to the next level of education.

Grammaticus

Between the ages of nine and twelve, gifted Roman boys from esteemed families would go to study with a grammaticus. Grammatici were teachers with more training, who would hone the skills that the students had learned in the earlier ludus school.

Students would examine poetry, literature, and the Greek language in greater depth to master those topics. They would also be given lessons in public speaking, which was an important skill among Roman elites.

These grammatici teachers were paid on a per-pupil basis and the most renowned of them became wealthy and respected members of Roman society.

Rhetor

At age fourteen or fifteen, the most gifted students would graduate from their grammaticus and go to study with another level of teacher called a rhetor. This was the final stage of the formal Roman education system, and very few boys would ever reach it.

Instruction at this level was focused on public speaking and further mastery of Latin and Greek meant to prepare students for careers as politicians or lawyers. There was a formal distinction drawn between training in language designed to advise or persuade, compared to training that was meant to understand complex texts, as in law or religion.

Additionally, there was training given in other abstract subjects, like geometry and mythology. This was designed to "flesh out" and provide a more rounded education for a student, instead of focusing purely on topics that would be needed for their chosen career path. This is similar to elective courses in modern-day universities.

Philosophy

A final level of education in Roman times that warrants a mention is the field of philosophy. In the ancient Roman and Greek worlds, philosophy was concerned with inquiry into the unexplained or abstract in a very practical sense. It often dealt with astronomical or natural observations that could be called rudimentary science.

Only the greatest Roman minds were concerned with philosophical topics. They strove to drive the enterprise of collective human knowledge forward, in much the same way that modern academics and scientists do today.

Related Pages: