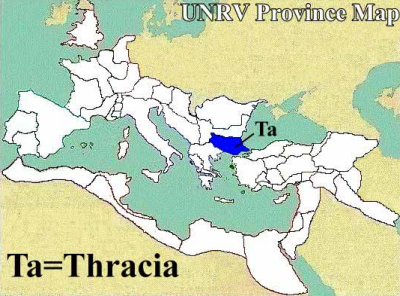

Thracia was the country east of Macedonia, bounded on the north by the Danube and on the south by the Aegean Sea, the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmora, and the territory of Bithynia.

In the beginning, the name "Thracia" was refered to in a very loose and vague fashion. Even the Macedonians were sometimes spoken of as a tribe of Thrace, which in that case simply meant the land north-east of Greece.

The Thracian tribes to the south, neighbouring the Ancient Greeks, determined the latter to name a so called Thrace region (now divided between Bulgaria, Greece and Turkey). Other names of ancient provinces inhabited by Thracians were: Moesia, Dacia, Scythia Minor, Bithynia (in northwest Asia Minor), Mysia, Macedonia, Pannonia, and others.

This area extends over most of the Balkans region, and the Getae north of the Danube as far as beyond the River Bug.

Archaeological and linguistic evidence supports the observation of Herodotus (5.3) in the fifth century BC, that the Thracians were a multitude of tribes who, despite a fundamentally common language and heritage, did not ever achieve a unified national consciousness. Aligning themselves in petty kingdoms and tribes, they never realized any form of national unity, except for short dynastic rules in the height of the Greek classical periods.

According to the ancient sources, of which they are limited, the Thracians were considered a primitive race. The mountainous regions were home to various warlike and ferocious tribes, while the plains were apparently more peaceable due to Greek contact and influence.

These indo-European people, while considered barbaric by their refined Greek neighbors, had developed advanced forms of music and poetry and other crafted arts, however. Most people lived simply in small open villages, and the concept of the urbanized city wasn't developed until the Roman period. Despite Greek colonization in such areas as Byzantium and Tomi, the Thracians avoided the urban life.

By the 6th century BC, Thracian infantry was heavily recruited by Greek states, and large deposits of gold and silver were mined. Persian advances into Eastern Europe a century later led to the introduction of many eastern customs, and the political domination of the region. Thracian mercenaries certainly fought against the Greeks under the Persian King Xerxes I during this time period.

One Thracian tribe, the Odrysae, led by their King Teres, did attempt a unification of Thrace as a single nation. A short dynastic rule lasted about a century until the takeover of Macedonian influence. Phillip II of Macedon, father of Alexander, invaded Thracia during his rule and made the whole of the region a Macedonian tributary.

This situation, ruled first by Philip, Alexander, Lysimachus and subsequent Macedonian kings, would last essentially until Roman intervention in the mid-second century BC.

Conflict between Rome and Thracia was unavoidable during the Macedonian Wars. The destruction of the ruling parties in Macedonia destabilized their authority over Thrace, and its tribal authorities began to act once more of their own accord.

After the battle of Pydna in 168 BC, Roman authority over Macedonia seemed inevitable, and governing authority of Thracia passed to Rome.

However, neither the Thracians nor the Macedonians had yet resolved themselves to Roman dominion, and several revolts would take place throughout this period of transition.

The revolt of the Macedonian Andriskus in 149 BC as an example, drew the bulk of its support from Thracia. Several incursions by local tribes into Macedonia continued for many years, though there were tribes who willingly allied themselves to Rome, such as the Deneletae and the Bessi.

The next century and a half saw the slow development of Thracia into a permanent Roman client state.

The Sapaei tribe came to the forefront initially under the rule of Rhascuporis. He was known to have granted assistance to both Pompey and Caesar, and later supported the Republican armies against Antonius and Octavian in the final days of the Roman Republic.

The familiar heirs of Rhascuporis were then as deeply tied into political scandal and murder as were their Roman masters. A series of royal assassinations altered the ruling landscape for several years in the early Roman imperial period. Various factions took control, with the support of the Roman Emperor.

The turmoil would eventually stop with one final assassination.

In 46 AD, the Thracian King Rhoemetalces was murdered by his wife, and the emperor Claudius put an end to autonomous client status. Thracia was incorporated as an official Roman province to be governed by Procurators, and later Praetorian Prefects.

The central governing authority of Rome was based in Perinthus, but regions within the province were uniquely under the command of military subordinates to the governor. The lack of large urban centers made Thracia a difficult place to manage, but eventually the province flourished under Roman rule.

Colonies were founded with one at Aprus (Colonia Claudia Aprensis) by Claudius or Nero, and at Deultum (Colonia Flavia Pacensis Deultum) under Vespasian.

Trajan expanded further on settling Thracia, just as he led the conquest of Dacia. Several new cities were founded during his rule, likely based on previous, yet smaller, population centers.

Late under the emperor Diocletian, the province was split into smaller regions for ease of authority, and more cities were built.

Military authority of Thracia rested mainly with the legions stationed in Moesia. The rural nature of Thracia's population, and distance from Roman authority, certainly inspired the presence of local troops to support Moesia's legions.

Over the next few centuries, the province was periodically and increasingly attacked by migrating Germanics. The reign of Justinian saw the construction of over 100 legionary fortresses to supplement the defense.

By the mid 5th century AD, however, as the Roman Empire began to crumble, Thracia fell from the authority of Rome and into the hands of the Germanics. With the fall of Rome, Thracia turned into a battleground territory for the better part of the next 1,000 years. Parts of the province would remain under the control of the Byzantines at least until the 13th century, but direct control was always in doubt.

Greek legend suggests that Orpheus, the benefactor of songs, singing and the lyre - an important cultural icon - was a Thracian. Spartacus, the slave who led the infamous uprising against the Romans between 73 - 71 BC, was also a Thracian. See the list below for more information on them and other famous Thracians:

Famous Thracians

Burebista was a king of Dacia between 70 BC - 44 BC. Under his rule, he united Thracians over a large territory, from today's Moravia in the West, to the Bug river (Ukraine) in the East, and from Northern Carpathians to Southern Dionysopolis.

Decebalus, a great king of Dacia, ultimately defeated by the forces of Trajan.

Dionysus, the Thracian god of wine, represents not only the intoxicating power of wine, but also its social and beneficent influences.

Orpheus, in Greek legend, was the chief representative of the art of song and playing the lyre, and of great importance in the religious history of Bulgaria and Greece.

Spartacus was a Thracian enslaved by the Romans, who led a large slave uprising in Italia in 73-71 BC). His army of escaped gladiators and slaves defeated several Roman Republican legions in what is known as the Third Servile War.