The end of Nero's reign, resulting from his extravagances and paranoid arrests, differed from the violent end of Caligula's reign in that there was no method of succession in place. While Claudius was certainly an unwanted choice by the Senate to replace Caligula, he did fill the role in a seamless transition that actually turned into a moderately successful reign.

With Nero's suicide, knowing that the military revolts of his generals and legions were irreversible, the Principate faced its first dangerous challenge of civil war since the great wars that ended the Republic.

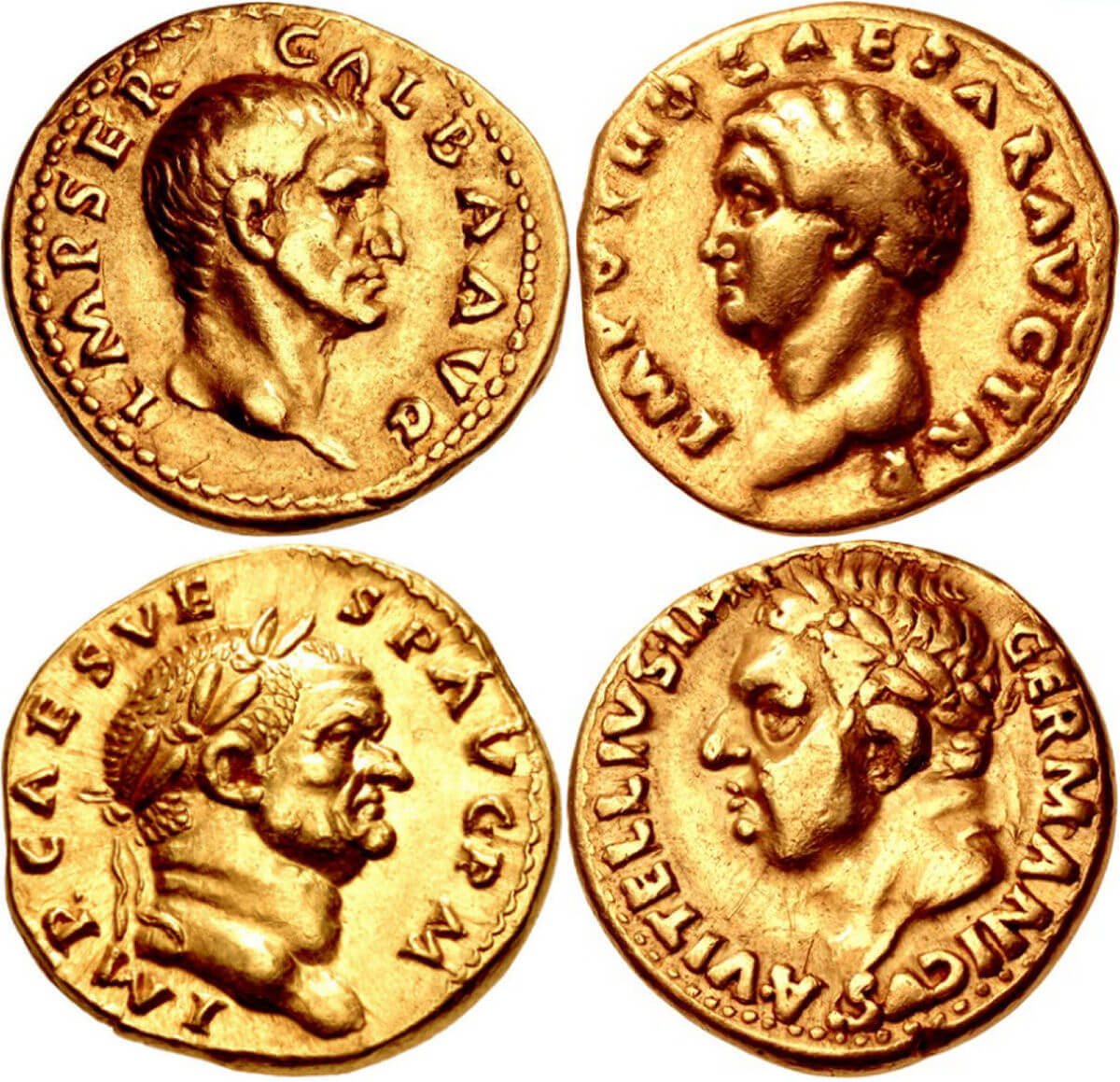

T8612, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Gold aurei coins of the four Roman emperors of 69 AD. Clockwise from top left: Galba, Otho, Vitellius, Vespasian.

In 68 AD, the revolt of Gaius Julius Vindex, governor of Gallia Lugdunensis, was the final catalyst that brought the Julio-Claudian line to an end. He was joined, in theory, by the powerful governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, Servius Sulpicius Galba (Galba never actually offered troops or support to Vindex), but their reasons are unknown. Its been speculated that both Vindex and Galba were on a very long list of targets for Nero's executioners, but this is impossible to prove.

Galba, too, has sometimes been incorrectly credited with attempting to take it upon himself to restore Augustan principals, but this also ignores some very specific and selfish behavior. Essentially speaking Galba, like the others who followed him, would soon show themselves as men of supreme personal ambition.

While Galba prepared to march on Rome, accompanied by Otho, the governor of Lusitania, loyal Neronian forces from the Rhine area under Lucius Verginius Rufus crushed the revolt of Vindex. What may have appeared to be a sudden disaster for the revolt of Galba turned into a fortuitous break. Rather than continue in their support of the crumbling Neronian administration, the forces of Rufus attempted to proclaim him as emperor.

In Africa, too, Clodius Macer, with the support of Galba, revolted with his one legion and began the process of recruiting another, while cutting off the grain supply to Rome and inciting the mob (Macer would soon be executed for his efforts by the distrusting Galba).

Though Verginius Rufus refused his troops declaration, preferring to let others play the imperial game, it was painfully obvious to Nero that any semblance of support for him had faded. (Verginius Rufus returned to Rome and was transformed into an inspiring, yet minor, player in the transition between emperors, and remained so even through and beyond the Flavian Dynasty.)

The Praetorian Prefect, Gaius Nymphidius Sabinus, played his own hand, promising his Praetorians a large reward for their allegiance to Galba, and Nero's fate was sealed. On 9 June 68 AD, Nero took his own life, and Galba marched to Rome with the adopted title of 'Caesar', where he was, for the most part, readily welcomed.

Thus began the concept of Caesar as a title in an attempt to legitimize Galba's candidacy , rather than a family name, which would be further defined to mean imperial heir in the near future.

Galba, despite his good fortune, made several decidedly devastating mistakes in his early reign. While on the march to Rome, he razed and/or plundered towns that refused his initial declarations as the new Roman emperor. Fostering this early atmosphere of distrust and anger did little to endear him to a population which would have readily accepted any strong and charismatic leadership.

Immediately upon his arrival in Rome, he continued Nero's terror of trying and executing members of the aristocracy that he thought were conspiring against him.

He also alienated the Praetorians and those legions that weren't under his direct command. Rather than pay the rewards originally promised by Sabinus (and understandably necessary under the circumstances) Galba refused to pay; perhaps in an attempt to rebuild the treasury, perhaps on a matter of principal, as the details are unknown.

Before long, the Rhine legions that had put down the revolt of Vindex refused to declare loyalty to Galba, and instead chose their new commander, Vitellius, on 1 Jan 69 AD.

Along with the news of the Rhine revolt, Galba was the victim of some terrible advice, and perhaps of his own convictions as well. Since Galba's march on Rome, Marcus Salvius Otho - the governor of Lusitania who had accompanied him - expected to be named heir to the throne as a reward for his part in the revolt's success.

Galba, however, likely wishing to prove his own sense of control, decided on Lucius Calpurnius Piso Frugi Licinianus instead. Otho, personally slighted, went directly to the Praetorian Guard, who were already unhappy with Galba, and bribed them to his own cause.

By 15 January 69 AD, the short six-month reign of Galba (who had actually only been in Rome since October) was coming to an end, and the Praetorians executed him in the Forum.

The Senate confirmed Otho as Galba's replacement and he immediately took over, having Galba's heir, Piso, killed as well. Though he was ambitious and perhaps guilty of greed, he did not follow up Galba's execution with a great deal more bloodshed.

Unfortunately though, he would have little time to prove himself a capable emperor as Vitellius, the newly appointed emperor of the Rhine legions, was on the march to Rome. Otho hastily gathered his forces and attempted to negotiate with the marching Vitellius, offering to make Vitellius his son-in-law. There was to be no deal however, and the rebel armies moved into Italy (Vitellius traveled behind the army in Gaul).

The two armies met at Bedriacum, where both jockeyed for position along the river. On 14 April 69 AD, Vitellius' legions broke through Otho's center and crushed any resistance. Otho, rather than flee and continue the civil war any longer, took his own life (ending his reign of only three months), and the Senate had little choice but to confirm Vitellius as the third emperor already of the year.

Vitellius was thus given an incredible opportunity to rebuild the dignity of the Imperial office and stabilize the Roman political situation, but instead he did little but dishonor Roman tradition and sensibility.

Romans killed in battle were denied proper funeral arrangements, and his legions marched in a state of drunken euphoria, creating havoc as they went. Vitellius arrived in Rome and honored himself and his friends with feasts, triumphs and games, much to the financial detriment of the treasury.

Though he smartly allowed for a gradual transition from military general to emperor, leaving significant power within the Senate and being lenient with Otho's supporters, his excesses reeked of similarities to Nero.

While contemporary sources are certainly favorable to Vitellius' eventual successor (Vespasian), therefore tainting their reports with propaganda, there is always some element of truth in the ancient reports. Accordingly, Suetonius described several examples of cruelty and depravity, setting the state for justifying continued civil war.

In July of AD 69, yet another revolt would spring up, this time in the east. Titus Flavius Vespasianus, an extremely successful general from the invasion of Britain and the pacification of Judaea, was about to accomplish what Vitellius could not: stabilization of the Roman Empire.

When Vespasian's forces marched on Rome, Vitellius attempted to flee the city, but was captured and executed by Vespasian's forces on 20 December 69 AD. With Vitellius' death, Vespasian became the new Roman emperor and ushered in a period of stability and prosperity known as the Flavian dynasty.

Did you know...

The 'Year of the Four Emperors' actually took about a year and a half... from the death of Nero in June 68 AD to the final accession of Vesapasian in December 69 AD.