Children in Ancient Rome

Due to the sophistication and level of technological advancement of ancient Rome when compared to other societies of the age, children experienced a level of protection and comfort that was rare in antiquity.

This meant that Roman children had many modern privileges, like schools and an extended childhood, that wouldn’t be common worldwide until the 20th century.

However, children in Rome still faced the constant peril and high mortality rates that characterized childhood in the ancient world.

Birth and Infancy

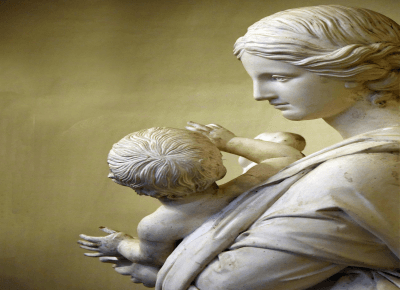

Pregnancy and childbirth had a huge cultural significance in ancient Rome. In fact, the raising of healthy children was seen as the goal of marriage and the primary public service that Roman women provided to society.

For this reason, pregnant women were treated with a number of natural herbs and drugs that supposedly helped increase the chances of a successful pregnancy. The development of midwives, who were trained specifically in the health of pregnant women and the birth process, further augmented these odds.

However, despite these significant advances, childbirth was still incredibly dangerous for both the infant and the mother in ancient Roman times. Stillborn children were quite common. Once a child was born, the midwives would examine the baby to ensure that he or she was healthy enough to survive. When a successful birth had been confirmed, it was a cause for celebration within the family and community.

Even after a healthy birth, it was still very common for a child to die early in life, which colored Roman cultural practices in a few ways.

First, a child was not given a name until several days after birth (eight days for girls, nine days for boys) because of the high chance of death over that time. Once this period had passed, there was a celebration ritual, called the dies lustricus, where the child was formally added to the family.

On this day, a child would be given a special amulet that was intended to protect them from harm and other evils. Boys were given a locket of gold, iron, lead, leather, or even cloth, called a bulla. Meanwhile, girls were given a moon shaped pendant called a lunula. Children would wear these amulets at all times until they formally reached adulthood.

Furthermore, children in ancient Rome did not receive legal protections and citizenship from the state until they were one year old.

The attitude of parents towards their children during these early stages would seem cold and distant by modern standards. Due to the high infant mortality rate in the ancient world, it was very common for parents to resist forming emotional connections with their children until they were relatively safe from the many lethal birth defects, diseases, and infections that so frequently struck young children.

As a result, there was almost no mourning period when a very young child died. As kids grew older, parents would bond more deeply with them until their relationship was more like it would be in a modern setting.

Childhood

Roman childhood was short by modern standards, lasting only until the age of puberty, which was deemed to be 12 for girls and 14 for boys.

Before the age of 7, both boys and girls were considered infants and remained in the care of their mothers or another caretaker almost all of the time. This was done in large part due to the fact that children of that age were still very vulnerable, especially in ancient times. Children this age lived largely carefree lives and had many toys that kids still play with today, like dolls, toy swords, balls, kites, and playhouses.

Children in the infant stage were considered too young to understand right and wrong and could not be charged with any crimes. Like modern children, they celebrated the anniversary of their birth date every year with family festivities. This was also when children learned most of the basic skills they would need for life in ancient Rome, usually directly from their parents.

At age 8, children could begin performing more activities outside of the home. This included school, which was mostly for boys, although some girls did receive a brief formal education. Both boys and girls could also begin working at this age, although the types of work were limited.

Unlike younger children, those between age 8 and puberty could be charged with a crime if it was deemed by the court that the child understood the wrongness of his or her action. However, punishments were very minor, usually amounting to a small fine.

Puberty and Transition to Adulthood

Childhood was slightly shorter for girls than for boys due to the fact that girls enter puberty at a younger age and are able to have children.

When a boy turned 14, there was an official ceremony where he would discard the tunic and bulla that were a symbol of his childhood and don a toga, which was only worn by men. The event was less noteworthy for girls, who were legally adults at age 12, but whose lives would change little from that time until they were married. At that time, she would get rid of her lunula and begin wearing the types of dresses worn only by adult women.

Related Page: Roman Clothing

Once children had passed this age, they were adults under Roman law and could be held legally accountable for their actions. They could also legally marry, although it was common for young Roman adults to wait a few years before marriage.

Pater Familias

Under Roman law, all children were legally subject to their father (or another male relative if the father had died), who was called the child’s pater familias.

The pater familias had complete control over the children, including whether or not he even accepted them as his own and allowed them to be included into the family and live in the house. Many children, sadly, were simply rejected and joined a class of orphaned outcasts.

Even when a boy turned 14, received his toga, and was recognized as an adult by the state, he still had to request to leave his father’s family to get married, found his own family, and become a pater familias in his own right. As for girls, their pater familias would automatically become their husband once they became married some time after turning 12.

While marriages for political or economic convenience were not uncommon, young Romans were generally allowed to marry who they pleased, although there was an entire strata of social classes that weighed heavily on this.

Young women also had the right to maintain their own personal wealth for their entire lives, meaning they could establish a modicum of financial independence from a very young age.