Since the treaty between Rome and Macedonia in 205 BC after the conclusion of the First Macedonian War, the two nations maintained an uneasy and fragile peace.

Rome was still occupied with Carthage, ending the war with the victory over Hannibal at Zama in 202 BC, and the continued hostile actions of Philip V of Macedon had to be temporarily overlooked. During the interim period between the First and Second Macedonian Wars, Philip took full advantage of Rome's apparent indifference.

Pasztilla aka Attila Terbócs, Marsyas, WillyboyDerivative work: Amphipolis, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

A map of the campaigns and battles of the Second Macedonian War

By 203 BC, Philip - having won some lands in Illyria during the first war - pressed his advantage in the region by gaining more territory in the Roman protectorate. Roman objections eventually changed Philip's tack, but moved him closer towards new conflict with Rome. He stretched his influence into the Greek cities to his south rather than Illyria in the north, which were formerly considered under the protection of Rome.

In 202 BC, Philip and Antiochus III of Syria entered into a secret deal to expand their own territories. The goal was to divide up the possessions of the Egyptian monarchy, which was embroiled in civil strife and under the rule of the child king, Ptolemy V. Antiochus moved against southern Syria and other parts of the current Middle East, while Philip turned away from Roman aggression to his west. His target was Thracia, and control of the important shipping lanes from the Black Sea to the Mediterranean.

By 201 BC, Philip was fully at war with the powerful fleet of the island-nation Rhodes, and with Attalus, King of Pergamum, in Asia Minor. Losses in battle to these nations inspired the Greeks, who had fallen under Macedonia's control, to rise up and appeal to Rome for help. A diplomatic mission from Pergamum, Rhodes and Athens arrived in Rome in the same year, all with the same goal of securing Roman intervention.

While initially rejected by the Senate, it soon became clear that Philip had to be dealt with, either in Macedonian territory at that point, or later after potentially building enough strength to invade Italy. Ambassadors were sent to Philip demanding his withdrawal from the territories of Rome's allies, which were flatly rejected.

By 200 BC, Philip sent one army to invade Attica, a territory belonging to Athens, while he commanded a force against coastal towns in Thracia. Further rejection of Roman demands to cease and desist prompted the declaration of war. Rome's stated reasons were to secure the independence of the Greek cities, but certainly also with the subversive goal to expand Roman influence in the east. In the same year, the Roman Consul, Galba, took command of two legions, and the Second Macedonian War began.

Late in 200 BC, Galba raided Macedonian border towns and moved to Illyria to undo some of Philip's gains there. A fleet was sent around the Greek coast to help them fend off Macedonian sieges, and the Aetolians were convinced to once again join the Romans against Philip.

Otherwise, the early campaign was rather uneventful, with neither side gaining much of an advantage. Galba and his successor, Publius Villius Tappulus, essentially spent two years in a virtual stalemate.

Titus Quinctius Flamininus ascended to command the Romans in 198 BC, and immediately set about taking the war to Philip. In negotiating with the Macedonian King, Flamininus championed the freedom of the Greek cities and demanded Macedonian withdrawal from all of Greece. Obviously refused, Flamininus did win the desired outcome... the entry of the Greek Achaean League into the war as allies of Rome.

Flamininus then engaged Philip at the River Aous and won a minor engagement which opened up an invasion route to Thessaly. With the avenue now open, the Romans moved into Macedonian territory and laid siege to several towns, until winter forced him to retire at Phocis until the spring.

Again the two parties met for negotiations late in the year 198 BC. Flamininus used his political savvy to set himself up for either future campaigning, or to end the war. Had he lost his Consular powers at the end of the year, and terms could have been negotiated to end the war, but if he won re-election, he wished to continue the fight.

Delaying Philip in the discussions, he had the Macedonians send an envoy to Rome to discuss the exact terms of peace. However, while the envoy was en route, Flamininus learned that he would in fact be keeping his Consular powers for the next season, and 'arranged' for the peace negotiations to fail in the Senate due to lack of popular support.

Newly inspired by his chance to win the war on the battlefield, rather than in the Senate, Flamininus set about planning for the next campaign.

Opening the spring campaign, Flamininus led his two veteran legions - along with a strong compliment (8,000) of mostly Aetolian Greeks - into Thessaly. Philip responded to the conquest of several of his regional towns by confronting the Romans with about 25,000 men. The two armies met at Cynoscephalae in 197 BC.

In the first large-scale meeting between the Roman Republican legions and the classical Macedonian phalanx, the legionary flexibility proved superior. Hemmed in by their own rigid tactics, the Macedonians were overwhelmed as Flamininus countered Philip's tactics with various strategic maneuvers. With a crushing defeat, Philip had no choice but to settle on unfavorable terms.

By the year 196 BC, the terms of the treaty were negotiated, and Philip had to give up all claims on Greek territory, sending the city-states into the protectorate of Rome. He also had to pay 1,000 talents in gold as tribute. He was, however, left in command of Macedonia. The Romans viewed Antiochus III in Syria (and who was now expanding in Asia Minor) as a considerable threat, and they viewed Philip as a capable leader able to provide a buffer. Terms of the treaty also included that all Greek cities in Asia Minor were now under the protection of Rome, clearly aimed at thwarting Syrian expansion into that territory.

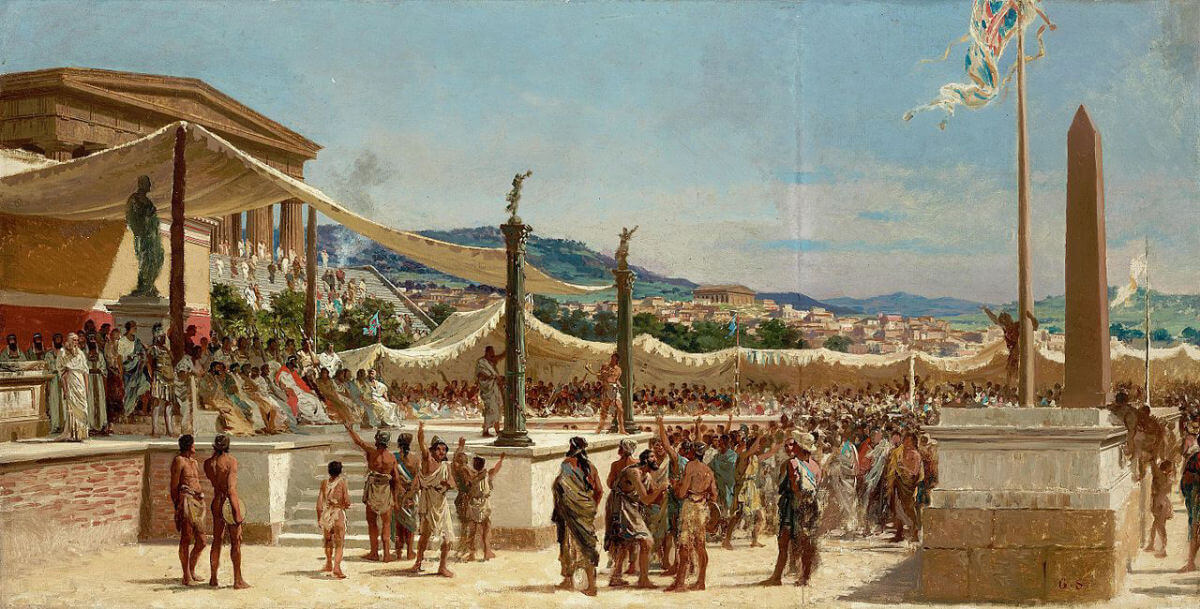

Rome, so soon after the end of the Second Punic War and with limited available manpower, wasn't able to continue to garrison the Greek cities, but the politically astute Flamininus used this fact of military necessity to Rome's advantage. At the Isthmian games in Greece in the summer of 196 BC, Flamininus announced the 'treaty of freedom'. Greece would be un-garrisoned by either Rome or Macedonia and they would be free to live their lives under their own laws and customs.

Winning great admiration from the Greeks that would last for centuries, Flamininus also accomplished another important goal. Unable to garrison the Greeks themselves, Greek admiration and gratitude to Rome for its part in defeating Macedon would secure their friendship and loyalty.

"Titus Quinctius offers liberty to the Greeks" by Giuseppe Sciuti, c.1879

Avoiding the quagmire of Greek politics, Rome expanded its influence in the east without the need for permanent legionary garrisons. By 196 BC, the Romans had removed all of their forces from Greece, while essentially gaining an obedient client kingdom and all the corresponding tribute that went along with it.

Punic Wars and Expansion - Table of Contents

- First Punic War

- Illyrian Wars

- Conquest of Cisalpine Gaul

- Second Punic War

- First Macedonian War

- Second Macedonian War

- Syrian War

- Third Macedonian War

- Fourth Macedonian War and the Achaean War

- Third Punic War

Did you know...

The Macedonian phalanx is an infantry formation developed by Philip II and used by his son, Alexander the Great, to conquer the Persian empire.