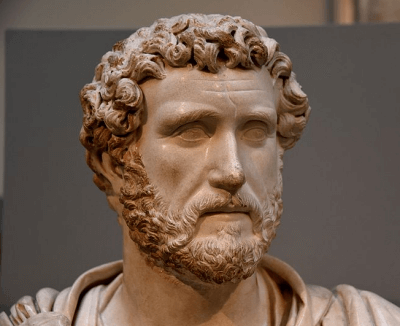

Antoninus Pius (86 - 161 AD)

Emperor: 138 - 161 AD

The rise of Titus Aelius Hadrianus Antoninus Pius, more simply known as Antoninus Pius, could be considered an unlikely yet fortunate turn of events.

His reign as Roman emperor, though far from one of perpetual peace as has often been described, was one of political stability, economic prosperity and consistent military strength.

Antoninus was born in September of 86 AD in the city of Lanuvium, very near to Rome. Despite his family heritage originating from Narbonensis (the southern coast of Gaul), his grandfather (Titus Aurelius Fulvus) had risen to the consulship twice and his father (Aurelius Fulvus) had served once in the same capacity.

To further cement the prestige and aristocratic lineage of his family, the future emperor's maternal grandfather Arrius Antoninus had also served two consulships.

When his father died at a young age, Antoninus was left in the care of his grandfathers. His mother, Arria Fadilla, remarried yet another man of consular rank, Julius Lupus.

Unfortunately, like his predecessors Trajan and Hadrian, there are few surviving written accounts for the life of Antoninus. For example, Cassius Dio's work is terribly fragmented, essentially leaving us with roughly six short paragraphs of unrelated (though still valuable) material.

The main source for Antoninus, the Historia Augusta, credited to Julius Capitoninus, provides much more detail, but has long been debated and questioned by scholars regarding its accuracy.

As such, little is known of the life of Antoninus prior to his accession. He was married to Annia Galeria Faustina, with whom he had four children (2 sons and 2 daughters). Though three of the children did not figure in imperial affairs, one daughter, Faustina the Younger, was later to marry Antoninus' nephew and adopted heir, Marcus Aurelius.

Antoninus seemingly rose in a typical fashion for a young man with his familial legacy, serving as quaestor and praetor before reaching the consulship under Hadrian around 120 AD.

Antoninus' rise under Hadrian continued with an appointment as one of four consular administrators of Italia, which included the territory encompassing Hadrian's own estates. By the early 130's AD, Antoninus' Senatorial career reached its pinnacle, when he was appointed governor of the prestigious Roman province of Asia Minor.

While the relationship between Hadrian and Antoninus is largely unknown, the course of the relationship took a decided and unexpected turn with the death of Hadrian's heir, Lucius Ceionius Commodus, in 138 AD.

Antoninus' position as a distinguished and respected proconsular Senator made him an attractive alternative, an alternative that would prove invaluable to uninterrupted succession and Hadrian's legacy (including his deification).

Hadrian named Antoninus as his second choice for adopted heir, with the condition that he in turn adopt his own nephew, Marcus Aelius Aurelius Verus (later Marcus Aurelius), and the son of Hadrian's first named heir, Lucius Aelius Aurelius Commodus (later Lucius Verus).

Antoninus was given time to consider the proposition (reflective of both his and Hadrian's effectiveness as leaders), before finally agreeing to the terms. Hadrian's new heir was effectively given joint imperial power, proconsular imperium and tribunician authority, allowing him to learn "on the job" before Hadrian passed away in July of the same year (138 AD).

Antoninus succeeded Hadrian at the age of 51 years old, likely not having been expected to reign for long (hence partly explaining the desire for him to succeed Hadrian with pre-determined heirs in place).

Unlike Hadrian, who succeeded Trajan under a cloud of uncertain legality regarding his adoption and with some political opposition, Antoninus' position had been sufficiently secured through the public adoption process.

Despite his complete absence of military experience (at least as far as the historical record provides) Antoninus would rule the empire for 23 prosperous and largely peaceful years (coupled with the reigns of Marcus Aurelius and his son/successor, Commodus, the peaceful uninterrupted succession would total some 55 years).

Unlike his predecessors Trajan, who campaigned for extended periods in Dacia, Armenia and Parthia, and Hadrian, who toured the provinces of the entire empire, Antoninus governed the empire almost exclusively from the city of Rome and the surrounding regional territory of central Italy.

A career politician and aristocrat, Antoninus seemed to be "at home" within reach of Senatorial peers, and embarked upon a reign consisting of conservative fiscal policy, diplomatic appeasement rather than aggression, and continued social welfare programs.

The Fourth Good Emperor

With the passing of Hadrian, Antoninus (whatever the true nature of the relationship between Hadrian and Antoninus may have been) immediately played the part of loyal adopted son.

Antoninus accompanied the body of the largely despised former emperor (at least in the view of the aristocracy) from Baiae to Rome, and saw to its placement within Hadrian's new tomb in the Gardens of Domitian.

His subsequent fight to have Hadrian deified and honored among the gods of the Roman Imperial Cult (as well as, and perhaps more importantly, pardoning Hadrian's opponents who may have been due for execution), earned him the cognomen of "Pius".

Numerous other honors were quickly voted for the new emperor including "pater patriae" (father of the country) which had been initially refused. Antoninus' wife Faustina was honored with the title Augusta (not an honor considered the norm for imperial wives) and was deified by her husband when she died three years later.

Antoninus' reign was one of conservative fiscal and building policies unlike both of his predecessors (Trajan and Hadrian). While Trajan and Hadrian built such great monuments as Trajan's Column, the Markets, the Pantheon, etc., Antoninus focused primarily on finishing the works of Hadrian (his Mausoleum for example) and making repairs to previously established public works.

The Colosseum, the Graecostadium, the ports at Caeita and Tarracina, the bath at Ostia and an aqueduct at Antium, as well as numerous roads and temples, were all works that saw restoration under Antoninus.

Economically, he showed reluctance for lavish expenditures, a stark contrast with some of his predecessors, such as the extravagant spending of Caligula for example. This freed the treasury for the essentials of running the state and making distributions to the people, without a need for increased tax revenues.

As such, he was able to return all the monies raised for his accession to the people of Italy, and half of all that was contributed by the provinces.

While Italy saw a renewed focus as the center of the empire (as Antoninus served his entire reign within Rome and nearby) in contrast to the campaigning of Trajan and the wanderlust of Hadrian, the provinces prospered as well.

Antoninus was strict with his provincial governors and tax collectors, tolerating only reasonable fixed collections from these provinces, and was open to hearing complaints against his procurators for excessiveness.

Antoninus seems to have held solid popularity with all three important elements of Roman politics: the aristocracy (Senate and Equestrian classes), the populace and the legions.

In the case of the Senate, he helped reverse the adversarial relationship set by Hadrian by including its members more freely in matters of advisement and routine government. Even more importantly, prosecution and execution of Senators virtually ceased during his reign.

In cases of provincial extortion, though he was quick to prosecute and sentence the guilty rather than confiscate their estates for his own use as in the past, he allocated these estates to the heirs of the guilty, provided that reimbursement was made to the provinces.

Only two men were noted for capital imperial punishment for treason under Antoninus. One of these two men, Atilius Titianus, was condemned though the entire affair was conducted by the Senate rather than as a dictate directly from Antoninus. A second man, Priscianus, apparently took his own life rather than face potential trial for aspirations to the throne, technically absolving Antoninus from the responsibility of execution.

In both of these cases too, unlike many incidents of potential treason during the principate, the emperor did not allow any additional investigation of the matter beyond the men in question. In essence, the cases closed with the deaths of the directly guilty, freeing their families and friends from possible implication.

In the case of the people, Antoninus won popularity through both traditional methods and his own generosity. Along with the aforementioned policies regarding collection of taxes and tributes, and despite the conservative fiscal style regarding the treasury, the emperor was open with his own private accounts.

A famine-induced shortage of wine, oils and grain was alleviated using purchases from his own private funds and distributed to the people.

New Laws were passed introducing protections for slaves and freedmen, as well as giving limited rights to women in cases of arranged marriage.

A new alimenta (a form of social program) was introduced in honor of his passed wife Faustina (the Faustinianae) which provided funds to care for orphaned or destitute girls.

Like most previous emperors, elaborate games were provided to entertain the masses. Great varieties of animals were displayed in these affairs including elephants, tigers, rhinoceroses, crocodiles and hippopotami.

In addition to the famine which he alleviated through his own donations, Antoninus won great respect and popularity for his reaction to various natural disasters. The collapse of some stands in the Circus Maximus, earthquake damage in Rhodes and Asia, destruction from fire in Rome, Narbo, Antioch and Carthage were all repaired, again through his own private funds.

Though the reign of Antoninus is often considered one of peace and general prosperity, the legions were in fact quite active. While the emperor did not lead campaigns himself or conduct military affairs like Trajan and Hadrian, his legates participated in a number of engagements.

In Britannia, Lollius Urbicus led a successful campaign north of Hadrian's Wall which re-established the border in Caledonia near the old line established by Agricola in the reign of Domitian.

A new wall, Antonine's Wall, which was to mark the northern limit of these conquests, was not nearly as elaborate as Hadrian's, but was an indication that the Romans meant for permanent occupation of the Caledonian lowlands.

Though the reasons for this campaign are not clear, it is certainly an indication that the Romans were not entirely at peace, nor resigned to the fact that the outer limits of the empire had been reached (as indicated by the reversal of Trajan's conquests under Hadrian).

In addition to the campaigns in Britain, the Moors in Africa were forced into peace, various Germanic and Dacian revolts or raids were checked, revolts in Achaea and Egypt were suppressed, and the Jewish uprisings from the time of Trajan and Hadrian were finally ended.

Despite the lack of actual military experience of Antoninus, a simple letter written by the emperor and backed by the reputation of the Roman military machine also caused the Parthians to abandon thoughts of a campaign against Armenia.

According to the Historia Augusta, Antoninus was widely respected both within and without the Roman empire, reporting that:

"No one has ever had such prestige among foreign nations as he, for he was ever a lover of peace, even to such a degree that he was continually quoting the saying of Scipio in which he declared that he would rather save a single citizen than slay a thousand foes."

At the age of 70, having reigned for 23 stable and prosperous years, Antoninus Pius died in 161 AD. As he was much loved, his death was mourned throughout all fabrics of Roman society.

Succession (as planned years before by Hadrian) was peaceful and without incident. Antoninus' adoptive sons Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus took up the mantle of authority in an unprecedented sharing of imperial power.

The ease of this transition (though relatively short-lived due to Verus' untimely death some eight years later) was a testament to both the foresight of Hadrian and the great administrative skills of Antoninus which made that transition appear so seamless.

Antoninus left the Roman treasury with an enormous surplus (in the millions of denarii) and left the bulk of his personal estate to his daughter Faustina the Younger (who had been married to Marcus Aurelius since 145 AD).

Despite the lack of glorious conquests often associated with periods of greatness, Antoninus' reign should be admired and revered for its noted lack of scandal, corruption and military disaster.

Antoninus was remembered by Marcus Aurelius in his work "Meditations" thusly:

"Be in all things Antoninus' disciple... Remember all this, so that when your own last hour comes your conscience may be as clear as his."

In light of the reverence paid by contemporaries and those that followed, this period in Roman history, while often overlooked by the modern world, could very well be considered as the greatest era of the Roman principate.

Did you know...

Young Antoninus was raised at Lorium, on the via Aurelia, where he later built a palace.

Did you know...

Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus erected a column of red granite in Antoninus' honor in the Campus Martius.